History and Chronicle

Established by Prof. Dr. Gert Reinhart

Continued by Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Thomas Pfeiffer

Translated by David Carnal

Heidelberg University was founded in 1386 by Rupert I, Prince-Elector of the Palatinate. From day one, the university was a hub for comparative law. Founding Rector Marsilius van Inghen, a Dutchman and jurist, had served as rector of the Sorbonne in Paris since 1367. Throughout the middle ages, famous scholars of comparative law taught in Heidelberg: François Baudouin (1520–1573) resided in Heidelberg between 1556 and 1561, importing the French school of Roman Law; Hugo Donellus (1527–1591, in Heidelberg 1573–1579); Charles Dumoulin = Carolus Molinaeus (1500–1560); Dionysius Gothofredus (1549–1622, in Heidelberg 1600–1620), Samuel Freiherr von Pufendorf (1632–1694, in Heidelberg 1661–1670), who held the Heidelberg Chair for Natural Law and International Law. Pufendorf married a bourgeois daughter of the city, receiving a prestigious house at University Square as a wedding present from the bride’s parents. Pufendorf’s Mansion stood on the grounds of today’s Institute. After some years in Heidelberg, he moved on to the University of Lund in Sweden. On 25 February 1803, the Final Recess of the Reichsdeputation (‘Reichsdeputationshauptschluss’) was passed: After the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, the Palatinate situated east of the Rhine fell to the Grand Duchy of Baden, including the cities of Mannheim and Heidelberg. Grand Duke of Baden Charles Frederick (1728 – 1811) passed new decrees for the organization of the university, which henceforth was called Ruperto Carola, bearing also the name of its founder Prince-Elector Rupert I (1353 – 1390).

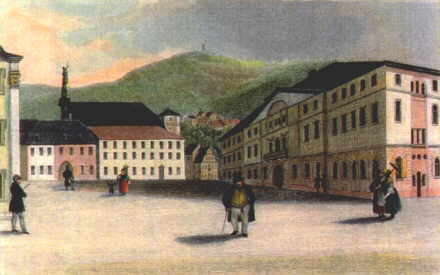

The ‘Land Law’ of Baden (‘Badisches Landrecht’) from 1809 is a de facto translation of the French Code civil of 1804, extended by additional rules with respect to the different social situation in Baden. Karl Salomo Zachariae von Lingenthal (1769 – 1843, in Heidelberg from 1807) was the most eminent and influential scholar of comparative law of his time, his Guide to French Civil Law (‘Handbuch des französischen Zivilrechts’) of 1808 influenced the legal development not only in Baden, but also in France and Italy. He was succeeded by Carl Joseph Anton Mittermaier (1787 – 1867, in Heidelberg since 1821), with whom von Lingenthal published the “Kritische Zeitschrift für Rechtswissenschaft und Gesetzgebung des Auslands” from 1829 on. Mittermaier had established a library that counted some 15.000 works on comparative law, generously granting everyman access to his home at Karlsplatz. Colleagues from all over Europe came to Heidelberg to study in Mittermaier’s library. His impressive collection remains wholly intact and is accessible at the University Library. A few years ago, Professor Erik Jayme coincidentally found a series of letters addressed to Mittermaier, contained in a suitcase at Palais Mittermaier; the letters reveal that this great scholar had a considerable impact on Anglo-American Law as it was shaped by Joseph Story and James Kent in the mid 19th century. Another professor who conducted studies in the field of comparative law, influencing the development of private law in the 19th century, was Johann Caspar Bluntschli (1808 – 1881). In 1840, Bluntschli was entrusted with the composition of the code for the canton of Zurich (‘Privatrechtliches Gesetzbuch für den Kanton Zürich’), which became applicable in 1856 and which was an important predecessor of the Swiss Code of Obligations (‘Schweizerisches Obligationenrecht’). To this day, Mittermaier and Bluntschli remain prominent names associated with Heidelberg, with a street and a metro station named after each of them.

After the formation of the German Reich in 1871, Heidelberg lost many distinguished scholars to what today is Humboldt University of Berlin, such as the jurist Bernhard Windscheid, whose concept of ‘Anspruch’ lies at the core of the German Civil Code (BGB).

Karl August Heinsheimer (1869 - 1929), son of grand-ducal Higher Regional Court Counsel (Großherzoglich Badischer Oberlandesgerichtsrat) Max Heinsheimer, published the Journal for French Civil Law (‘Zeitschrift für französisches Zivilrecht’) between 1883 and 1892 and followed in his father’s footprints. He became a judge at the Heidelberg Regional Court (‘Landgericht Heidelberg’), habilitated himself at the Faculty of Law and, after a period as interim professor, held the Heidelberg Chair for the Private Law of the (former) State of Baden, German Civil, Commercial and Procedural Law from 1907 on. His prime aspiration, the institutionalization of Comparative Law within the Heidelberg Faculty, had been unsuccessful for financial reasons. Later, in 1916, Heinsheimer found a benefactor in the royal Prussian Councellor of Commerce (‘Kommerzienrat’) and Eldest of the Berlin merchants, Carl Leopold Netter, a relative to his father’s second wife.

The deed of foundation is an enlightening account against the enthusiasm for war of the ruling elites of the times. The faculty decree on the establishment of a Seminar for Comparative Law was approved by Frederick II, Grand Duke of Baden, on 15 December 1916. Heinsheimer was named Director of the ‘Seminar’, Netter donated 100.000 German gold marks as foundation endowment and 25.000 marks for reconstruction and furnishings. The Insitute was inaugurated on 1 April 1917 at Augustinergasse 9. On 23 April 1918, Carl Leopold Netter established an endowment professorship; the Faculty appointed Friedrich Karl Neubecker, a student of Heinrich Dernburg and the famous comparative legal scholar Josef Kohler, on 1 October 1918.

Ever since, there have been two chairs and two departments in the Institute: Chair of Heinsheimer = department of “Rechtswirtschaft” (‘economic law’; later: International and Foreign Business Law) und the Chair of Neubecker = department of Comparative Law (later: International and Foreign Private Law).

In 1916, Heinsheimer stated as the Institute’s mission: Law in action (Commercial Law, Company Law, Law of Legal Persons), Comparative Law and, based on the latter, Harmonization of Law.

Neubecker, dying unexpectedly in 1923, published a German translation of Tore Almén’s three-volume Scandinavian Sales Law.

Inflation slashed Netter’s initial endowment. The Seminar was made an Institute of Heidelberg University and has since been receiving funding through the State budget. The foundation for Economic and Comparative Law as launched by Netter in 1916, however, continues to exist and contributes to the financing of research at the Institute. Today, Professor Thomas Pfeiffer serves as chairman of the foundation.

When founding the Institute, Heinsheimer had big ideas, such as the publication of “Contemporary Civil Codes” (‘Zivilgesetze der Gegenwart’), which consisted of the original codes and their German translation: In swift succession, the civil laws of Brazil, France and England were issued. Work on the civil codes of the Scandinavian States and Russia had reached an advanced stage when it was suspended in 1933. In 1926, Max Gutzwiller of Switzerland was appointed as Neubecker’s successor. Heinsheimer was elected Rector in 1927. Under his rectorship, the Neue Universität complex was built, a joint project with Jacob Gould Schurman, Ambassador of the United States in Berlin, who had studied law in Heidelberg. Schurman raised funds for the building’s construction from Heidelberg alumni in the United States. On the occasion of Heidelberg University’s 625th anniversary, donations from abroad contributed to the splendid modernization of the central lecture hall building. Heinsheimer died on 16 June 1929.

Max Gutzwiller took over the lead of the Institute, founding the “Studies on Private International Law and Comparative Private Law” (‘Beiträge zum Internationalprivatrecht und zur Privatrechtsvergleichung’), editions 1 – 7. In June 1936, Gutzwiller was released of his duties after refusing government orders to divorce from his wife, who was affected by racial laws. His family emigrated to Switzerland, finding shelter in St. Gallen for one year. Eventually, he returned to a Chair at Fribourg, where he had taught before coming to Heidelberg ten years earlier.

Gutzwiller’s successor, Eugen Ulmer, was in charge of the Institute as its only director. When Ulmer heard that the “Führer” of the University had given orders to remove from the Rectorate all portraits of former Rectors of Jewish descent, he managed, in an adventurous journey, to escort the canvas with Heinsheimer’s portraiture to Switzerland, from where it was shipped to Heinsheimer’s widow and their children in New York.

After the outbreak of World War II, the Institute was renamed Institute for Foreign and Public International Law (‘Institut für ausländisches Recht und Völkerrecht’), consisting of two sections, namely the Department for Public International Law headed by Carl Bilfinger and the Department for Foreign and Private International Law led by Eugen Ulmer. In 1943, Bilfinger accepted a professorship in Berlin, where he was director of the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut (today’s Max Planck Institut) for Foreign Public Law and Public International Law in addition to his Heidelberg Chair. Faced with a full-on war, Bilfinger evacuated the Institute’s complete library stock to Heidelberg.

Heidelberg University was reopened in the late autumn of 1945. Walter Jellinek, who had been discharged by the National Socialists in 1935, headed the International Law department; Eduard Wahl, who had been dismissed by the National Socialists in 1943 for an alleged affiliation with the student resistance group “The White Rose” (‘Die weiße Rose’) centered around the Scholl siblings and their friends, ran the Department for Foreign and Private International Law with Eugen Ulmer. During those years, Heinsheimer’s oldest son returned the portrait of his father that Ulmer had sent to New York. We cherish the painting, in memory of Karl August Heinsheimer and Eugen Ulmer.

Since Bilfinger had relocated the library of the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institute from Berlin to Heidelberg, it seemed natural to separate the Department for International Law from the Institute and unite it with what today is the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law in Heidelberg, for a return to the Berlin City Palace, located in East Berlin, was out of the question.

Ever since, Heinsheimer’s Institute has been centered on private law again. Under the responsibility of Eduard Wahl, the first major project was the harmonization of German family law with democratic principles and the realization of gender equality. Eugen Ulmer accepted the appointment to a Chair in Munich, where he served as superintendent of the newly founded Max Planck Institute for Foreign and International Patent, Copyright and Competition Law.

Rolf Serick, who had been working at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative and International Private Law , which was then located in Tübingen, followed in Wahl’s Chair. His lifelong theme was the law of credit securities in modern business law: the reservation of title and collateral assignments; six volumes and supplements were published. Professor Nagata from Tokio, who translated Serick’s works into Japanese, was a frequent guest at the Institute.

Eduard Wahl engaged in politics: From 1949 – 1969, he was a directly elected member of the German parliament for the constituency of Heidelberg, later becoming first Vice President of the Council of Europe as well as member of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Western European Union. His main field of interest was the study of French Law and – following the tradition of his great teacher Ernst Rabel, the most eminent German scholar of comparative law in the 20th century – the discipline of Comparative Law, with a special emphasis on Sales Law. To relieve Wahl, a third Chair was created, which was first entrusted to Kurt Niederländer, professor for the history and comparison of Law. During the unsettled times in the aftermath of 1968, he was Rector of Heidelberg University for many years. After Niederländer retired, the third chair was incorporated into the Institute for German and European Corporate and Business Law (‘Institut für deutsches und europäisches Gesellschafts- und Wirtschaftsrecht’).

In 1959, a Department for Foreign and International Business Law (‘Ausländisches und internationales Wirtschaftsrecht’), led by Eduard Wahl, was added; funded externally by German industry, the Antitrust Act from 1958 was critically researched. A department for the ‘Law of Developing Countries’ was established in 1964, led by Professor Omaia Elwan of Cairo until his retirement; his main focus has been and continues to be Islamic Law. The library was extended by adding a new aisle to the building in order to cope with the growing number of books. The Institute’s structure which was designed at the time persisted for many years; in the meantime, it has been replaced.

By and by, the Institute saw a change of directors: Peter Schlechtriem was appointed to Wahl’s chair, he was followed by Detlef König, who, after his sudden death, was replaced by Erik Jayme. During Jayme’s years, the Institute became a center for the discussion of fundamental questions of Private International Law and Comparative Law, such as the relation between cultural identity and Conflict of Laws or the influence of postmodern culture on Private International Law.

Gert Reinhart, who had been assistant to Eduard Wahl in the 1960s and as Academic Director knew the Institution’s history like no other, administered the Institute until his retirement in 2001. In his work, he focused on the harmonization of private law. Reinhart’s work is continued by Nika Witteborg-Erdmann.

Rolf Serick was followed by Michael Will, who was replaced by Herbert Kronke in 1993. Herbert Kronke was appointed Secretary General of UNIDROIT in 1998 and hence was put on leave until 2008. After returning to his Heidelberg chair, Kronke developed an international teaching network in the field of Transnational Commercial Law and as Dean of the Law School established a cooperation with the Law Faculty of the University of Luxembourg in the field of Capital Markets Law. In March 2002, Thomas Pfeiffer from Bielefeld took over the chair of Erik Jayme. When Burkhard Hess left Tübingen for a Chair for Procedural Law at Heidelberg in April 2003, Thomas Pfeiffer engaged Professor Hess as third director of the Institute. Their collaboration brought about various highly noted studies on European Procedural Law commissioned by the EU Commission and different federal government ministries.

2012 was a year of changes. Herbert Kronke was called to serve as permanent arbitrator and chairman of chamber three in the Iran-United States Claims Tribunal in The Hague. Although he is on leave of absence in Heidelberg for this commitment, Professor Kronke remains on the board of the Institute’s directors. The same year also saw the appointment of Burkhard Hess as director of the newly founded Max Planck Institute for International, European and Regulatory Procedural Law in Luxembourg. Hess continues teaching in Heidelberg as honorary professor.

As of 1 July 2014, Marc-Philippe Weller, a former Professor at Freiburg Law School, holds Kronke’s chair. Since 1 August 2014, Christoph A. Kern, who formerly held the Chair for German Law in Lausanne (Switzerland), has been holding the Chair for Private Law and Procedural Law.

At present, the professors’ research is primarily focused on problems in European and international private and procedural law, international business law, comparative law and harmonization of law.

From 1967 to 2001, research results were published in some 32 volumes of “Heidelberg Studies in Comparative and Business Law” (‘Heidelberger rechtsvergleichende und wirtschaftsrechtliche Studien’); today, the director’s collectively publish the series “Private Law – Business Law – Procedural Law” (‘Privatrecht – Wirtschaftsrecht – Verfahrensrecht’). Commemorative publications for Max Gutzwiller, Eugen Ulmer, Eduard Wahl, Hubert Niederländer, Rolf Serick and Erik Jayme are a testament to the high reputation of the honorees.

Three scholars of the Institute are among the editors of the journal IPRax (‘Practice of Private International and International Procedural Law’). The Yearbook of Italian Law (‘Jahrbuch für italienisches Recht’), the Lindenmaier-Möhring series (a collection of annotated rulings by the Federal Court of Justice of Germany [BGH]), the journal “Rechtswissenschaft” and the journals ZEuP and ZGR are published by members of the Institute, the directors of which also issue the annual “Reports on Joint Seminars of the Montpellier and Heidelberg Law Faculties” (‘Berichte über die Gemeinsamen Seminare der Rechtsfakultäten von Montpellier und Heidelberg’).

In recent years, many full professors have emerged from the Institute for Comparative Law, Conflict of Laws and International Business Law: Christoph Benicke, Martin Gebauer, Stefan Huber, Heinz-Peter Mansel, Götz Schulze, Boris Schinkels and Matthias Weller.

All academic staff (professors, lecturers, research assistants) teach courses at the Faculty of Law. The Institute provides mentoring for ca. 100 ERASMUS-fellows from approximately 50 partner faculties and many of the LL.M. students. With Thomas Pfeiffer, a director of the Institute was responsible for the University’s international relations, serving as Vice Rector between 2007 and 2013.

It has always been the directors’ desire that the many guests from all around the world may not only successfully conduct research, but feel comfortable and homey at this time-honored site that is the Institute for Comparative Law, Conflict of Laws and International Business Law at Heidelberg University Faculty of Law.